Fuzhou Pinghua: Telling Ancient Stories in the Local Dialect, Revealing Fuzhou’s Timeless Charm

Highlight

Fuzhou Pinghua is a traditional form of storytelling delivered in the Fuzhou dialect. It blends spoken narration with melodic chanting, accompanied by cymbal and gong interludes, earning it the title of a “living fossil of folk vocal art.” Fuzhou Pinghua, which evolved from Northern storytelling traditions, took shape in the late Ming to early Qing dynasties. It is the most widely embraced folk art form in the Fuzhou dialect area and was officially inscribed in the first batch of the National Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2006.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, listening to Fuzhou Pinghua was one of the “three beloved pastimes” cherished by locals. Today, despite the rise of new entertainment options leading to an inevitable decline in audiences for traditional arts, there are still passionate individuals committed to preserving and carrying on these cultural legacies. Amid the sound of cymbals, the ancient charm blends with youthful energy, giving rise to a fresh vitality…

“Living Fossil” of Folk Art

On April 20, which happened to fall on a weekend, the “Weekend Theater Encounter”—a public welfare performance series delivering high-quality cultural and artistic resources from Fujian directly to grassroots communities—held its special Fuzhou folk art event in the Shangxiahang Historical and Cultural District.

Xie Qiuping was performing

The streets bustled with crowds, while on stage, the performers were completely immersed in their art. Backstage, Xie Qiuping, a storyteller from the Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi Training Institute, waited for her cue, occasionally tapping the cymbals tied with red silk ribbons in her hands.

Dressed in traditional costume, a young performer from the institute explained to the audience: “Fuzhou Pinghua is a form of storytelling delivered in the Fuzhou dialect, combining spoken narration with melodic chanting. It preserves the vocal traditions of the Tang and Song dynasties while weaving in the distinctive expressions and rhythms of local speech, earning it the title of ‘a living fossil’ in the world of folk arts.”

Fuzhou Pinghua is known as a “living fossil” in the world of folk arts due to its profound historical roots. According to oral traditions passed down by generations of performers, Fuzhou Pinghua originated around the Tang and Song dynasties and took shape during the late Ming and early Qing periods.

Amid the chaos at the end of the Tang dynasty, many storytellers from the Central Plains migrated to Fujian, bringing with them northern traditions of scripture chanting and oral storytelling that gradually took root in the region. According to the Yuan dynasty writer Tao Zongyi’s description in Nan Cun Chuo Geng Lu, around the late Song to early Yuan period, the famous storyteller Qiu Jishan from Lin’an came to Fuzhou to perform. His style, known as “Shi Zan-style narration,” began with poetic recitations and included cymbal interludes. This historical record shows that by that time, storytelling was already flourishing in Fuzhou, with northern folk storytelling styles like the poetic “Shi Zan” narration having been introduced to the city.

In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, Ju Fucheng, the foremost disciple of the famous Jiangnan storyteller Liu Jingting, visited Fuzhou’s Shuangmenlou twice to teach and perform. Local performers enthusiastically embraced his methods, adopting Liu’s storytelling style along with stage props like folding fans, wooden clappers, and cymbals. This marked a shift from the traditional “Jiangqing” style—which involved straightforward narration of classical novels—to a new approach that blended spoken narration with singing, mixing rhythm and prose. Over time, Fuzhou storytelling evolved into a distinctive art form rooted in historical tales, folk legends, and urban literature, while incorporating elements of poetry, folk songs, and popular melodies, resulting in a vibrant and innovative performance tradition.

Xie Qiuping performed Fuzhou Pinghua in the Shangxiahang Historical and Cultural District.

“The next Pinghua performance is The Legend of Xiaoyi Lane, which recounts a quarrel between two neighboring official families in Fuzhou’s Gulou District, sparked by a dispute over a shared wall…” The host went on to guide the audience through the performance.

As the sharp sound of the wooden clapper echoed from the stage, the lively crowd went quiet immediately. With only a table, a cymbal, and her presence, Xie Qiuping’s solo performance began.

With her left hand, she gently held a bamboo stick, tapping it rhythmically between the table and cymbals, the crisp sound echoing like pearls softly falling onto a jade surface. In her right hand, the jade thumb ring struck the cymbals in a steady beat, producing a tone as pure as gold and jade.

The cymbal in Xie Qiuping’s hand is a distinctive hallmark of Fuzhou Pinghua. Unlike other storytelling traditions that use a variety of props, Fuzhou Pinghua features a folding fan, a thumb ring, clappers, a silk handkerchief, a bamboo stick—and uniquely, a single cymbal. According to legend, during the Qing conquest, musical instruments were banned, so performers used just one cymbal that symbolized a divided nation where music could never be fully played.

“The Minjiang River flows endlessly, and this cultural city is rich with stories. Our story begins at Dongjiekou in Fuzhou, where a small patch of land sparked a big dispute.” As the opening lines were sung, the bright melody flowed like a fresh spring, instantly drawing in passersby. People paused to listen, some even taking a seat near the stage, while the crowd gathered closely, snapping photos and filming the performance.

Throughout the performance, Xie Qiuping expertly shifted between spoken narration and melodic chanting, seamlessly adjusting her voice to reflect the story’s twists and the emotions of the characters.

A defining characteristic of Fuzhou Pinghua is its blend of spoken narration and melodic chanting, which distinguishes it from other regional storytelling styles. “The chanting comes in three forms: Xutou (introduction), Yinchang (singing), and Supai (storytelling),” Xie Qiuping told the reporter. Xutou is used to begin the performance, setting the tone, calming the audience, summarizing the content, and introducing the theme. Yinchang conveys the characters’ inner thoughts and emotions. Supai is used when characters share their backgrounds or pour out their feelings.

As the story progressed, Xie Qiuping’s narration flowed effortlessly, spilling out like a steady stream of beads, while the cymbal in her hand grew faster and more vibrant. When the performance concluded, a sharp crack of the clapper rang out, and the audience erupted into thunderous applause.

In the end, the two families reconciled, each giving up three feet of land—six feet in total—forming what is now known as Xiaoyi Lane. With a subtle lift and gesture of her bamboo stick, the storyteller transported the audience through time, letting them experience firsthand the birth of this cherished tale.

Down-to-earth Folk Art

In the past, “bathhouses, storytelling places, and tea stalls” were affectionately called Fuzhou’s “three leisure treasures.” During the 1980s, listening to Pinghua was one of the city’s favorite pastimes. Nearly every street featured a storytelling place, where rows of reclining chairs were almost always filled to capacity.

Inside the storytelling venue, with nothing more than a few simple props—a table, a folding fan, a clapper, a bamboo stick, and a single cymbal—the storyteller brings tales of the past and present to life with eloquent words and vivid narration. Today, thanks to the “Weekend Theater Encounter” public-welfare performances, people in Fuzhou can once again savor the old-fashioned charm: sipping jasmine tea, reclining in a rattan chair, and enjoying a lively session of Pinghua.

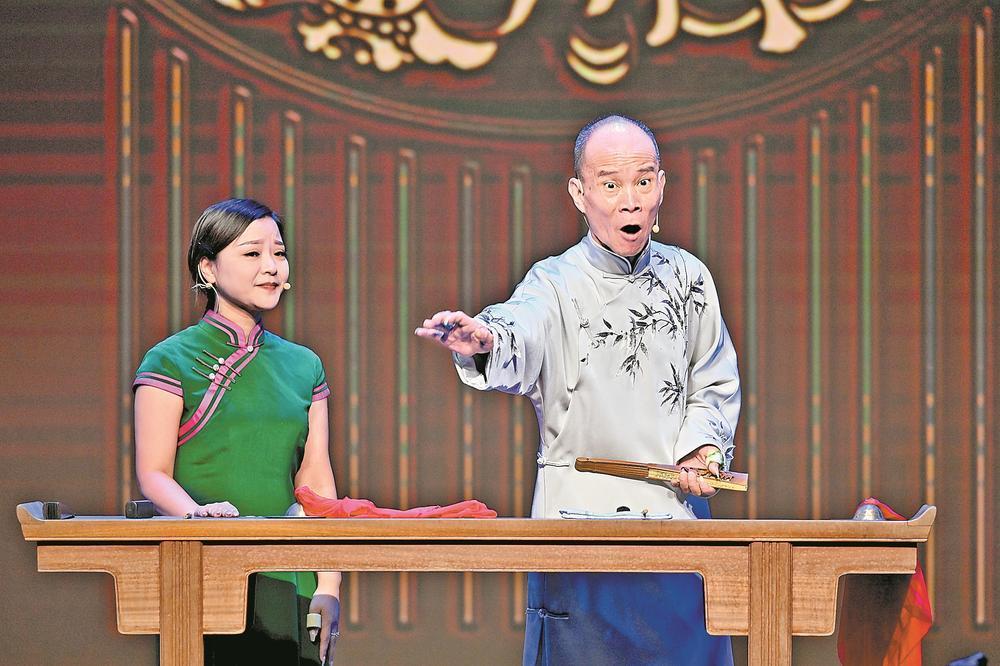

Photo of Ye Zhaochen in Performance

This is exactly the kind of performance setting most familiar to Ye Zhaochen, a national-level representative inheritor of Fuzhou Pinghua, an intangible cultural heritage.

Sometimes his eyebrows would lift with enthusiasm, other times knit in deep thought; his voice shifted in tempo and tone, while his hands moved expressively... When chatting with the reporter about Fuzhou Pinghua, Ye Zhaochen spoke with great passion and ease. Although he has rarely performed on stage since recovering from a stroke, whenever the topic of Fuzhou Pinghua comes up, the 64-year-old still radiates the energy of the vibrant storyteller he once was.

“Fuzhou Pinghua is like the ‘light cavalry’ of traditional folk arts—it’s the most approachable and relatable to everyday people,” Ye Zhaochen said. He noted that its performance style is very flexible, requiring no costumes or elaborate sets. With just a simple table and a chair, the storyteller can showcase their talents.

Ye Zhaochen hails from a long line of Pinghua storytellers. His father, Ye Yiqing, studied under Chen Chunsheng, one of the “Three Masters” of Fuzhou Pinghua, and was later honored as one of the “Eight Kings” of the art form. Together with Su Baofu and Wu Letian, he was celebrated as one of the “Three Elders of Pinghua.”

“My father made his stage debut at 13, performing a story about a little prodigy. Since he was so short back then, he had to stand on a stool just to reach the stage,” Ye Zhaochen recalled. Ye Yiqing skillfully tapped the cymbal with a bamboo stick, producing crisp, clear sounds. His chanting and gestures were so spot-on that the audience cheered, ‘This boy is a prodigy too!’ From that moment, the nickname “Little Prodigy” caught on and spread far and wide.

In Ye Zhaochen’s recollection, whenever his father was invited to perform, he would host the story’s author at their home around noon. Over a shared meal, the author would outline the story, and within about half an hour, his father would have a solid understanding of the material. By the time he took the stage that evening, he could effortlessly deliver a two- to three-hour performance. His smooth mix of storytelling and singing won continuous applause, with audiences often urging him to return the following evening.

“In the past, Fuzhou people would invite Pinghua storytellers to perform at weddings, funerals, festivals, and religious ceremonies,” Ye Zhaochen said. Many of his contemporaries, when looking back on their childhoods, fondly recall the Pinghua performances they grew up with.

The period from the 1960s to the 1980s was the heyday of Fuzhou Pinghua. At its peak, Fujian boasted over a hundred Pinghua venues and more than 300 storytellers. It was common for two or three performances to take place simultaneously, just a few hundred meters apart, filling the streets and alleys with vibrant storytelling.

“What the locals love most are the folk tales rooted in Fuzhou’s oral traditions and folk legends. By weaving in regional slang, folk songs, and two-part sayings, the storytelling becomes more engaging, lively, and truly reflective of the local culture,” said Ye Zhaochen.

“In the past, storytellers went from village to village, performing their tales door to door. Today, we bring folk art performances straight to grassroots communities and neighborhoods,” said Chen Feng, head of the Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi Training Institute. He shared that the institute now runs five regular public welfare folk art venues at Wuta Guild Hall, Baqi Guild Hall, Yushan Xiyutai White Tower, Luzhuang Community Ancient Alley, and Junmen Community. Together, these venues host more than 200 free performances each year.

Steadfastness amid Decline

The new venue of the Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi Training Institute is located at the intersection of the Shangxiahang Historical and Cultural District and the “Heart of the Minjiang River” Youth Square, one of Fuzhou's latest landmarks. Every Friday evening, the first-floor hall comes alive with lively activity.

At around 7 p.m. on April 18, the reporter arrived at the Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi Training Institute. Before the performance started, the hall was almost packed, with more than thirty seniors chatting comfortably in the local dialect.

As the performer prepared to take the stage, he warmly greeted the longtime fans in the Fuzhou dialect before settling behind the wooden table. At 7:30, the clang of the cymbal marked the timely start of the “Rongcheng Performance.”

“Rongcheng Performance’ is a regular, ongoing public welfare show held at our institute,” Chen Feng explained. “Currently, our audience mainly consists of older Fuzhou residents. We aim to take advantage of the new venue’s proximity to popular tourist attractions to make ‘Rongcheng Performance’ a vibrant showcase of Fuzhou’s traditional folk arts, attracting passersby and visitors to discover Fuzhou Pinghua through our shows.”

Like many traditional art forms, Fuzhou Pinghua has gradually lost its appeal among modern audiences due to the rise of movies, TV, mobile games, and short videos. Its space in the entertainment market has steadily shrunk—from a time when nearly every household would invite a storyteller for a performance, to now relying on public welfare shows to stay relevant. This shift highlights the challenges Fuzhou Pinghua faces in finding its place in today’s fast-changing cultural landscape.

Performance Photo of The Water-Scarce Family

In 2006, Fuzhou Pinghua was recognized as part of the first batch of national intangible cultural heritage. The project description notes that Fuzhou Pinghua faces serious challenges in sustaining and developing itself in the modern era, and calls for greater support and protection.

Liu Yiwei, a provincial-level representative inheritor of Fuzhou Pinghua, has seen the rise and fall of the art form. He recalls that back in 1979, when he applied to join the Fuzhou Folk Art Troupe, more than 200 people competed for spots in the Pinghua program, with only 14 ultimately accepted. But by 2006, when Fuzhou Art School offered a Pinghua class, each cohort could barely attract two or three students, making it impossible to continue regular instruction. The program was eventually discontinued.

“Nowadays, many young people in Fuzhou can’t speak the local dialect, and that’s the biggest obstacle to preserving and developing Fuzhou Pinghua,” said Liu Yiwei. In his struggle to keep the art alive, he came to realize that the fading of the dialect is one of the key reasons behind Pinghua’s decline.

Chen Xiaolan, President of the Fujian Provincial Folk Artists Association, believes that the core of preserving Fuzhou Pinghua lies in staying true to its roots and maintaining its unique artistic identity. Regardless of how the form evolves, at its essence it must remain a storytelling art performed in the Fuzhou dialect, blending spoken narration with singing.

Established in 2019 as a fully funded public institution, the Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi Training Institute has since welcomed a large number of university students into its programs.

“In recent years, many of the young performers at the Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi Training Institute come from outside Fuzhou. Experienced teachers patiently guide them through mastering the local dialect, and these young actors learn every word with dedication. Their commitment is evident in hundreds of performances and numerous awards, establishing them as key figures on Fuzhou’s folk art stage,” Chen Xiaolan said. “Despite the challenges they face, Fuzhou’s folk artists stay focused on doing what they need to do.”

A Generational Relay for the Folk Art Preservation and Promotion

Young Pinghua performer Zhang Fangyuan performed a Fuzhou Pinghua segment in the community.

Zhang Fangyuan, a young actor born after 1995, is a newcomer at the Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi Training Institute.

Recently, the reporter met Zhang Fangyuan in Luzhuang Community, Guxi Street, Gulou District, Fuzhou. At 3 p.m., the sharp clang of the cymbal rang out from the community’s multipurpose activity room as Zhang performed The Tragic Tale of Ruiyun, a classic Fuzhou Pinghua piece, for the local audience.

Inside the activity room, Zhang Fangyuan sat behind a modest desk, holding a cymbal raised in his left hand while rhythmically striking it with a bamboo stick in his right. The ring on his thumb gently touched the cymbal, creating a clear, lingering vibrato as he narrated a tale of righteous heroes and bravery.

“Fuzhou Pinghua is a performing art that engages directly with the audience, requiring interaction and responsiveness to their feedback. Practicing ten times offstage can’t compare to a single live performance,” Zhang Fangyuan told the reporter. He is still building his performance experience. Watching from the audience, his mentor Ye Zhaochen focused closely, gently tapping his fingers to the beat.

“Fuzhou Pinghua originally had no scripts or written records; it was passed down entirely through oral tradition, from teacher to student,” Ye Zhaochen explained. Zhang Fangyuan has been studying with him for three years, often going to his home every week for lessons. He would recite each line and demonstrate each gesture, while Zhang diligently memorized the words and learned the movements, step by step.

Before getting involved with Fuzhou Pinghua, Zhang Fangyuan studied percussion at the School of Music, Fujian Normal University. In 2020, he took part in the “China Intangible Cultural Heritage Inheritors’ Training Program · Fujian Folk Art Workshop,” which marked the beginning of his journey with Fuzhou Pinghua.

“When I first watched Senior Sister Xie Qiuping’s Supai cymbal performance, it felt familiar. It reminded me of my percussion studies,” Zhang Fangyuan recalled about his initial encounter with Fuzhou Pinghua. After graduating from university, he joined the Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi Training Institute as a performer, beginning his journey as a devoted preserver of the art.

Liu Yiwei performed at the opening ceremony of the Maritime Silk Road International Culture and Tourism Festival.

Liu Yiwei, a senior artist, has dedicated his life to Fuzhou Pinghua. He has witnessed the rise and fall of Fuzhou Pinghua and has spent years tirelessly working to preserve this traditional art form.

While many Pinghua artists have moved on to other careers, Liu Yiwei has kept seeking new ways to revitalize Fuzhou Pinghua. He performed in the live streaming for the prominent Fujian cuisine brand “Mindu Fu Banquet,” assisted the Publicity Department of the CPC Gulou District Committee, Fuzhou in producing the music video Fuyun Gulou, appeared in the documentary Exploring Fuzhou produced by the Fuzhou Municipal Bureau of Culture and Tourism, and helped integrate Fuzhou Pinghua into the feature-length historical documentary Kai Min.

In August last year, Liu Yiwei appeared in the major Fuzhou folk art production The Water-Scarce Family, which was featured at the 3rd National Puppet and Shadow Show Exhibition held in Handan, Hebei.

Under the dazzling stage lights, accompanied by the emotive singing of the folk artists, Liu Yiwei, clad in a long robe, took the spotlight as a Pinghua performer. With his signature deep, smoky voice, he recounted the story of how the Fuzhou municipal government addressed the water shortage problem for the residents of Tengshan Alley in the 1990s. The blend of Fuzhou Pinghua and Chiyi became one of the most captivating highlights of the performance.

“Everyone agrees that this staging format works really well. In addition, we display subtitles on the LED screen so that even audience members unfamiliar with the dialect can easily follow the story,” Liu Yiwei said.

On December 6 last year, the Maritime Silk Road International Culture and Tourism Festival opened in Fuzhou. Liu Yiwei appeared at the opening ceremony dressed in a pink long robe, portraying a Fuzhou Pinghua storyteller. He joined Luo Weizhe, a “Chinese Bridge” contestant from Hamburg, Germany, dancer Lin Shumin, artisan Hai Ruo, and Taiwanese entrepreneur Guo Yifan as ambassadors promoting tourism in Fuzhou.

“Fuzhou celebrates the Maritime Silk Road International Culture and Tourism Festival. With picturesque scenery along the Minjiang River and a vibrant cultural hub, this coastal city shines brightly on the world stage.” On stage, Liu Yiwei combined singing and storytelling in a theatrical performance that showcased Fuzhou’s cultural richness and tourism growth, offering the audience an immersive experience of Fuzhou Pinghua’s unique charm.

“The original lines created by the director team were lengthy and lacked rhyme,” Liu Yiwei explained. Throughout the creative process, he focused on ensuring the vernacular lyrics adhered to the rhyming patterns of the Fuzhou dialect, highlighting the distinctive features of Fuzhou Pinghua. The content also reflected the cultural and tourism characteristics of Fuzhou, such as “cultural axis,” “picturesque Minjiang River,” and “charming coastal city.”

“The Fuzhou dialect preserves ancient pronunciations and characters, making it a unique cultural treasure. I’m actively working on new scripts inspired by modern life, aiming to integrate Fuzhou Pinghua into people’s everyday lives. Preserving and advancing our local traditional art is a responsibility I take on without hesitation,” Liu Yiwei said firmly.

Now, Liu Yiwei always keeps a stack of script drafts in his bag, covering a wide range of topics, including Fuzhou’s cultural tourism, “Fu culture,” and public-interest litigation of the procuratorate. He often takes out the drafts to revise them or jot down new ideas, the worn, creased pages quietly bearing witness to his unwavering dedication to the art. (Fujian Daily Reporter: Jiang Fengman; Intern: Chen Jiangrui; photos are provided by the interviewee unless otherwise credited)