Lu Meisong: Tracing the Origins of the Central Axis of Fuzhou

Author: Lu Meisong

Author: Lu Meisong

In China, the central axis of a city serves as both an important symbol and a fundamental element of urban architecture, shaping a distinctive feature and traditional norm of urban architecture. It highlights the unique characteristics and aesthetic values of Chinese architectural culture. The concept of the central axis can be traced back to ancient times, originating from the city layouts of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, where it embodied principles of symmetry and reflected the ethical and moral values embedded in palace and temple architecture.

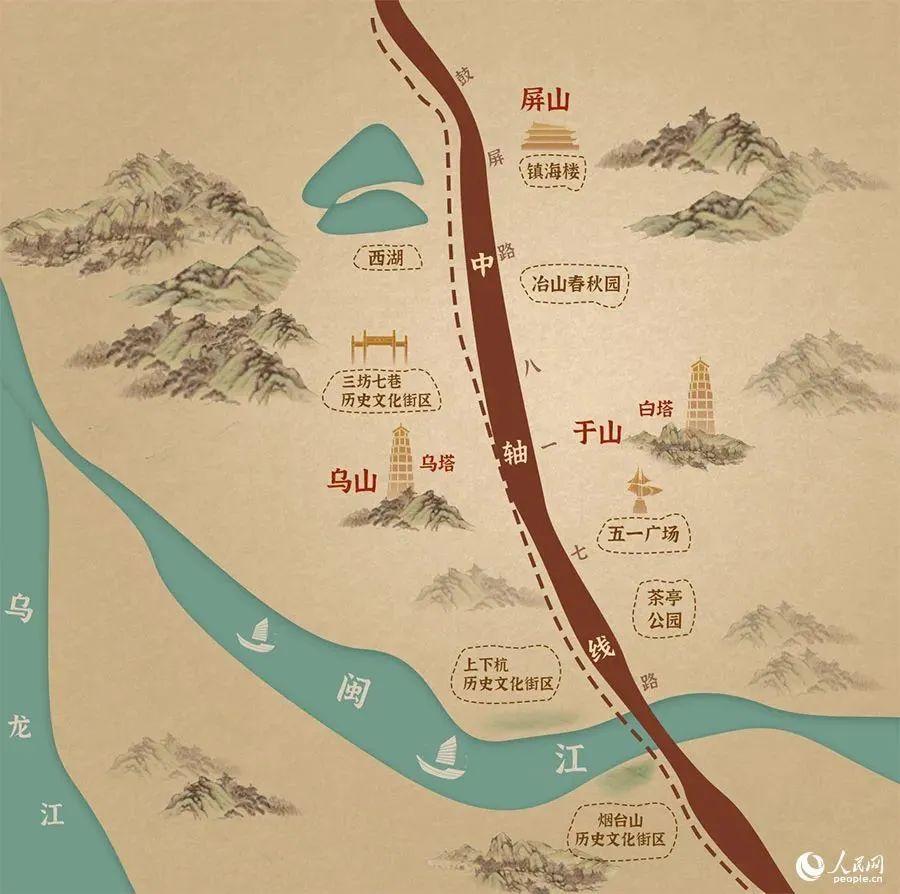

Photo Source: People’s Daily Online (people.cn), by Jiao Yan

The origins of Fuzhou’s urban development date back to the Han Dynasty, when the capital of the Minyue Kingdom was built, modeled after Chang’an, the imperial capital of the time. Although archaeological studies at Yeshan have yet to fully reconstruct or illustrate the ancient city’s layout, excavations at the Han-era ruins in Chengcun Village, Wuyishan City, provide valuable insights into the architectural style and overall structure of the royal city. This also offers evidence of the architectural layout and design characteristics of Yecheng, the first capital of the Minyue Kingdom, built at Yeshan in Fuzhou. As both the royal city ruins at Wuyishan and the Minyue capital at Yeshan were constructed during the same period — a time when King Yao of Minyue and King Yushan of Dongyue ruled concurrently — it can be inferred that both cities were largely modeled on the layout and planning principles of Chang’an, the imperial capital of the Western Han Dynasty. This reflects the emergence of Great Unity and the shaping of a unified cultural identity during the Han era.

The origins of Fuzhou’s central axis can be traced to the construction of Zicheng of Jin’an Prefecture, built by Yan Gao, the first governor of Jin’an during the Western Jin Dynasty. Historical records note that Yan Gao approached the project with great care, selecting the site with the guidance of the famed geomancer Guo Pu. He chose an auspicious location on the former site of the Minyue Kingdom’s capital and followed the design principles of Han and Jin dynastic capitals: the main buildings faced south, administrative offices were symmetrically arranged to the east and west, and a central street ran through the city. Built on elevated ground, the city overlooked the southern expanse of government offices, residential quarters, and military barracks. By the Tang and Song dynasties, government officials such as commandants (tuan lian), surveillance commissioners (guan cha shi), supervisory commissioners (chu zhi shi), and defense commissioners (fang yu shi), along with provincial and prefectural military and administrative leaders, including the provincial governor (zhi lu) of Fujian, prefectural governors (zhi zhou), regional inspectors (ci shi), military governors (du du), and transport commissioners (zhuan yun shi), all continued the tradition of establishing their official offices along the southern slope of Yuewang Mountain.

According to the Yuewang Mountain Gazetteer, “the Chief Military Commission during the Tang and Five Dynasties was located between the northern side of the Drum Tower (Gulou) and the southern slope of Yeshan, covering the middle section of Guping Road and its surrounding area. During the reign of Emperor Taikang in the Jin Dynasty, it served as the administrative center of Jin’an Prefecture. In the Tang Dynasty, it became the Chief Military Commission of the Center, and during the Five Dynasties period, it was elevated to the Grand Chief Military Commission in the Later Liang period.” The Chief Military Commission was established in the second year of the Shangyuan era (761) of the Tang dynasty, and by the eighth year of the Xiantong era (867), it was reorganized into the Office of the Surveillance Commissioner (guan cha shi). In the third year of the Tongguang era (925) of the Later Tang Dynasty, it became the headquarters of the Weiwu Military Commission (jie du shi). In the third year of the Jianyan era of the Song Dynasty (1129), it was elevated to a military governor’s office. During the Hongwu period of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1398), it became the office of the provincial administration commissioner (bu zheng shi). In the sixteenth year of the Kangxi era of the Qing Dynasty (1677), the position of Provincial Administration Commissioner was formally established, and the site thereafter served as the commissioner’s office. After the founding of the Republic of China, it was burned down.

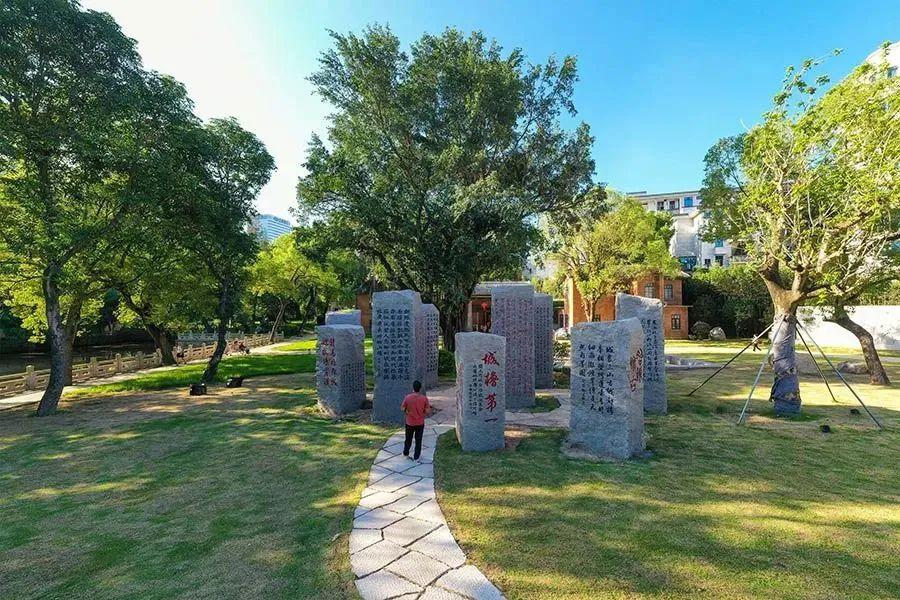

Yeshan Chunqiu Park, situated at the northern end of Fuzhou’s central axis, is an important part of the city’s historical and cultural heritage, serving as an important birthplace of Minyue culture. (Photo by Huang Hai; Source: Fujian Daily)

The formal establishment of Fuzhou’s central axis dates back to the Tang Dynasty. The northernmost point of Fuzhou’s historical central axis during the Tang Dynasty was the Chief Military Commission of the Center, which traced its origins to the administrative office of Jin’an Prefecture in the Western Jin Dynasty. During the Later Liang period of the Five Dynasties, it was elevated to the Grand Chief Military Commission, and in the Later Tang period, it was converted into the headquarters of the Weiwu Military Commission (jie du shi). In the third year of the Jianyan era of the Song Dynasty, it was elevated to a military governor’s office. During the Hongwu period of the Ming Dynasty, it was converted into the office of the provincial administration commissioner (bu zheng shi), a function it retained throughout the Qing Dynasty. After the founding of the Republic of China, it was burned down. The site of the prefectural office was used continuously through the Jin, Tang, and Song dynasties, and it was not until the Yuan dynasty that the General Administration Office was formally established at Qiaolou (the Drum Tower). During the Tang and Song periods, the Chief Military Commission compound included dozens of courtyards, halls, buildings, terraces, chambers, verandas, and pavilions, covering a vast area. It truly served as a grand starting point for the city’s central axis.

Since ancient times, Yuewang Mountain, located north of the city, has been the administrative center of central Fujian. During the Jin Dynasty, Yan Gao, the first governor of Jin’an Prefecture, carefully initiated the construction of city walls and official residences there—meticulously selecting the site based on geographic features and geomantic advice. Nearly two millennia have passed since. Following the establishment of the official seat, successive rulers—whether emperors, prefectural governors, magistrates, or imperial officials—have consistently regarded this location as a highly auspicious and strategic site. Consequently, government offices have been continuously established and maintained here despite changes in officials and shifting political powers. This tradition continues to the present day. The reason lies in the old saying: “Officials who have served in many regions, with extensive experience, all agree this place is the best.” The ancients regarded this area as a place where high official status and strategic geographic significance perfectly aligned. For this reason, Fuzhou has long been known as a key gathering center. This is truly rare within the nine ancient regions of China. It is entirely fitting that the provincial capital’s central axis begins here.

Since the Tang Dynasty, following the north-high, south-low terrain of Yuewang Mountain’s southern slope, the offices of the Chief Military Commission, the Weiwu Military Commission, and the Hujie Gate were arranged in sequence. The Hujie Gate was originally the southern gate of Zicheng built by Yan Gao. South of the gate flowed the Hujie River, which served as the city’s moat (today’s Hujie Road). South of the Hujie City Tower, four city towers were built in a row from north to south. The first was the Huanzhu Gate Tower, protected by the Dahang River and connected via the Dahang Bridge. Further south stood the Lishe Gate Tower, which faced the Lishe River—now known as the Antai River—that served as the city’s moat. This tower originally marked the southern gate of Luocheng, built by Wang Shenzhi, King of the Min Kingdom. Continuing southward, Wang Shenzhi later expanded the city by adding an inner fortified section called Jiacheng, featuring the Dengyong Gate, also known as Ningyue Gate and commonly called the “South Gate” today. During the Song Dynasty, the outer city was expanded with southeastern and southern walls, pushing the city boundaries outward to Hesha Gate, which faced the Xima River, now known as the Dongxi River. During the early Ming Dynasty, under the governance of Wang Kegong, Shicheng was rebuilt into a solid fortress. Fuzhou’s city walls came to feature seven city gate towers and seven moats stretching from north to south. Including the Sanjie River (also known as the Dadao River) and the Minjiang River outside the city, Fuzhou was affectionately known as the city encircled by nine “jade belts.”

Because successive governors established their offices along the southern slope of Yuewang Mountain and named the main street in front of the offices “Xuanzheng Street,” the avenue extending southward from this street came to be known as Xuanzheng South Street (commonly called South Street). This route ran from the Chief Military Commission southward through Hujie Gate, Huanzhu Gate, Lishe Gate, all the way to Ningyue Gate (today’s South Gate), corresponding to the present-day Guping Road connecting to 817 North Road. Outside Huanzhu Gate (now Dongjiekou), the main road extended in two directions: to the east, it was known as the Left Road, now Dongdajie (East Street), and to the west, as the Right Road, now Yangqiao Road. South of Ningyue Gate (the South Gate), the road extended beyond Hesha Gate to today’s 817 Middle Road, continuing the central axis of Xuanzheng Street.

As for the road stretching from Hesha Gate to the old Diaolongtai and the Xinshi embankment, during the Tang and Song periods, it was likely no more than an earthen path through open fields, used by carriages, horses, and pedestrians. At that time, it would have been difficult to establish a formal central axis. By the Song Dynasty, the accumulation of sand and silt along the Minjiang River gradually formed sand banks on the northern shore. As the sandbars, including Lengyanzhou, Shangxiahang, and Taijiang Wharf, solidified into land, they gradually replaced the Xinfengshi embankment as the new commercial hub and bustling marketplace. Only then did the southern central axis of Fuzhou begin to shift toward the area between Zhongting Street and Wanshou Bridge. Even so, the areas surrounding Diaolongtai—Shangxiahangzhou, Cangxiazhou, Bangzhou, and Yizhou—remained bustling trade and logistics hubs, though their commercial roles had shifted.

Shangxiahang Historical and Cultural District. (Photo by Reporter Ye Cheng)

The central axis extending southward from Yuewang Mountain, anchored by Fuzhou’s city gate tower as a key landmark and running through the city, forms a main thoroughfare stretching ten li. It stands as a testament to Fuzhou’s urban expansion, thriving commerce, and dynamic logistics throughout history. This is, of course, a different kind of central axis with its unique characteristics and style, unlike those of major metropolises such as Beijing and the ancient capital Xi’an, which serve as political, economic, and international cultural centers.

Notably, the seven enclosed city gate towers within Fuzhou are connected and intersected at their center by a main thoroughfare running north to south. Established during the Tang Dynasty, this thoroughfare—called Xuanzheng Street—served as the administrative heart where official decrees and political authority were announced. To the south, it extends directly to the end of Xuanzheng South Street, commonly known as South Street. Indeed, the administrative offices within the city, first established with the construction of Zicheng, have a history of over a thousand years. Historical records still offer us a glimpse of their original design. The poet Du Fu once lamented in a poem reflecting on the past, “Among rivers and mountains his old abode—empty his writings; Deserted terrace of cloud and rain—surely not just imagined in a dream? Utterly the palaces of Chu are all destroyed and ruined; The fishermen pointing them out today are unsure.” Today, the historical landmarks that once lined the central axis can only be imagined through fragmentary accounts in historical records, as much of the original landscape has been lost. Even so, such a preserved axis remains rare among China’s many historical cities.

The presence of a central axis in cities reflects the shared aesthetic ideals and urban planning principles of the Chinese nation. Modern China is a continuation of its historical past, and Fuzhou is a part of the great expanse of China. China has long embraced the fundamental belief that “All the land under heaven belongs to the ruler, and all officials governing the territory serve under his authority.” This idea is deeply ingrained in the traditional mindset of the Chinese people and is reflected equally in their political, economic, and cultural values. Architecture is frozen art and a tangible reflection of cultural ideals. The ancient buildings and traditional crafts of Fuzhou truly embody this spirit. Unfortunately, only a few traces of this heritage have survived to the present day.

Yu Shan built Diaolongtai on Huize Mountain (today’s Damiao Mountain). (Photo by Reporter Ye Cheng)

Additionally, the outward extension of Fuzhou’s central axis also reflects the inheritance and development of the city’s historical architecture. Cheng Shimeng, a Song Dynasty poet and official who served as the Surveillance Commissioner of Fujian and Prefect of Fuzhou, once used a vivid metaphor to describe the city’s seven towers. He wrote, “The seven towers soar toward the sky,” vividly conveying their majestic height and dynamic presence. Even more interesting is that Huang Shang, a top-ranking scholar who served twice as Fuzhou’s Prefectural Governor, wrote a poem containing the line “The seven towers stretch directly toward Diaolongtai.” This reflects the contemporary belief that the central axis connecting the seven city towers within Fuzhou all pointed straight to Diaolongtai on Damiao Mountain (formerly Huize Mountain) in Taijiang. Within this central axis visual corridor, Xuanzheng Street in Fuzhou’s inner city extends directly outward toward Diaolongtai.

Ancient people were so keen on telling stories about Diaolongtai because of its long-standing history and the famous stories associated with the Wuzhu family. As early as the Tang Dynasty, Fuzhou was recognized as the “Prosperous Prefecture of the Southeast” and hailed as a key strategic hub in the region. It ranked among China’s major provinces, bustling with overseas trade and lively cultural exchanges. The maritime and river (Minjiang River) ports for external navigation were likely situated near Diaolongtai. At that time, the alluvial plain along the northern bank of the Minjiang River had not yet formed, and ports or ferry docks had not yet been established. In fact, fixed sandbars only began to develop after the Song Dynasty. Records of these ports and markets along the Minjiang River during the Tang and Five Dynasties can be found in the poetry of those eras. Tang poet Ma Dai (who died in 869) composed a five-character regulated verse titled Farewell to Attendant Censor Li on His Appointment in Fujian. The poem conveys roughly this meaning: The ancient capitals of Jin’an and the Yue Kingdom lie beneath a tangle of wild grasses, but Diaolongtai still stands. Cranes gather on the Qintai Pavilion. Under the bright moon, broad waves roll, and coastal mountains rise in the distance. Guests arrive in boats adorned with orchids, welcomed by southern monks descending stone steps. Wisps of cloud and mist bring dampness, while solitary islets mirror the low-hanging sails. The honored guests, full of poetic inspiration, compose verse as the cries of autumn monkeys echo through the night. Why did the poet choose to focus so much of the imagery on Diaolongtai when writing this farewell poem for Attendant Censor Li’s appointment in Fujian? An analysis of the poem suggests that, at the time, Diaolongtai was the most prominent landmark of Fuzhou, the political center of Fujian. It was steeped in legend — from the temple honoring Wuzhu, King of Minyue, to the tale of Yushan fishing for a white dragon—and preserved traces of the ancient Minyue Kingdom and Jin’an Prefecture, including the old palace, fishing islet, Qintai Pavilion, and flocks of cranes. Perhaps even more important were the bustling river ports where ships arrived and departed, the guesthouses (known as binfu) that hosted travelers, and the stone steps where monks from distant lands came ashore—features that set Diaolongtai apart from any other place. The poem also richly evokes the natural scenery of Fuzhou’s waterways and coastline: surging waves, coastal landscapes, distant mountains, drifting mists, mirrored sails, and the calls of gibbons. In particular, the reference to the “solitary islet” clearly identifies Diaozhu and Longtai as prominent ports and ferry landings. The poem reveals the poet’s deep and detailed understanding of Fuzhou’s history and cultural heritage, which was quite rare given the limited geographic and informational access available at that time. Another Tang Dynasty poem conveys a similar scene. In Farewell to Shen Guang on His Journey to Fumou by Li Dong (died in 897), the lines read: “As the tide rises, the governor hosts a feast, while the pearls glimmer as the island monk makes his way back.” The poem depicts the Surveillance Commissioner (guan cha shi) of Fujian, as the chief official, bidding farewell to a distinguished monk at a riverside banquet, likely held near Diaolongtai along the Minjiang River.

During the late Tang and early Five Dynasties period, Weng Chengzan, who was twice dispatched to Fuzhou to confer the title to Wang Shenzhi, expressed his deep emotions about returning home and reconnecting with his friend. His poem, titled Farewell at the Xinfengshi Embankment, reads: “On the Yonglou Tower, the music halts for a while. At the Xinshi Embankment, I lift my cup once more. The sorrow of parting lingers heavily in my heart. When suddenly, I hear the imperial decree granting my return. For now, I must part from dear ones. But today, I carry the imperial edict home. How fortunate that the eldest branch is still alive, and that the land now feels closer to the Diaolongtai.” The poem conveys several important points: by this time, the area beneath Diaolongtai in Taijiang had evolved into the thriving district of Xinfengshi (or Xinshi). This suggests that the location had become a bustling commercial center, serving as a vital junction for both land and water routes. It was a key port for trade, acting as a crucial gateway linking Fuzhou to both the upper and lower stretches of the Minjiang River, as well as to overseas destinations. Beneath Diaolongtai, embankments were built and buildings constructed, turning the area into a vibrant marketplace. This spot became a vital junction on the main road heading south from Fuzhou. It was here that imperial envoys and vassal state rulers would exchange heartfelt farewells, highlighting the importance of this location. Notably, Governor Huang Shang highlighted, “The seven towers stretch directly toward Diaolongtai,” indicating that the seven main roads in the city all converged on Diaolongtai and Xinfengshi. This firmly establishes the location as the southern end of Fuzhou’s central axis. To the south, across the river, lies Longtanjiao, home to a shrine dedicated to Xuanwu, the northern water deity. Known as Wangbeitai, this shrine symbolically aligns with the deities worshipped at the Zhenhai Tower on Pingshan Mountain in later years. Therefore, the author suggests that the central axis of Fuzhou’s ancient city (or city gate tower) ran along Xuanzheng Street, which was located in front of the official buildings during the Tang and Song dynasties. To the south, this axis extended into Xuanzheng South Street, reaching the South Gate (originally known as Ningyue Gate) and Hesha Gate, which today corresponds to Guping Road and 817 North Road. Beyond the South Gate, the city’s axis stretched towards Chating Street, passing by the “Han-era Minyue Tombs” and the ancestral temple. It then curved around Yangtoukou, turning into Yangzhong Road and Yanping Road, ultimately reaching the bustling ancient street known as the Xinfengshi Embankment beneath Diaolongtai in Taijiang. This area, home to guesthouses and restaurants, was a vibrant hub of trade and social life. Although the path may have been slightly winding and veered a bit to the west, the area’s commercial prosperity, heavy traffic, and dense population make it clear why it served as the southern end of the city’s central axis.

File Photo: Zhongting Street, Fuzhou (Photo by Reporter Bao Hua)

After the Song Dynasty, with the emergence of islets and the construction of floating and stone bridges across the river, a direct connection was established between Zhongting Street and Shahe Bridge, making it much easier to travel from the Minjiang River into the city. Along the way, bustling markets and flourishing cultural and religious buildings began to spring up. Over time, this area naturally evolved into a vibrant new commercial district in Fuzhou.